Articles

Published in South Florida Hospital and Healthcare Association Newsline – Over the years, those of us who have worked in healthcare for a while have seen, heard, and used our share of buzzwords and industry lingo. Terms like “population health”, “value-based care”, and “social determinants of health” have worked their way into the healthcare vernacular and have actually resulted in moving the industry away from an episodic, disease-specific treatment model toward a more holistic, more comprehensive system of improved access, better clinical outcomes, enhanced continuity of care, and greater efficiency. The most recent buzzword that I have begun noting in the healthcare literature has to do with the “digital transformation” of the healthcare delivery system. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were signs that the industry was considering how to innovate and better engage with patients, providers, and community members with existing and potential digital tools. The novel coronavirus pandemic limited in-person interactions between providers and patients, and we all witnessed the explosion in telehealth visits, but we also saw a resultant increase in interest in digital technologies to support remote visit scheduling, contactless payments, and use of artificial intelligence and digital analytics to track COVID’s progression from community to community. All of this leads me to my central question: What exactly is this “digital transformation” of healthcare? And, secondly, what specific technologies are being considered and adopted by healthcare providers? There are a several ways to classify and analyze digital transformation. Many of the digital technologies are complementary to one another, and, even as I write this, these technologies are ever-changing and new ones are evolving. Nonetheless, one needs to start somewhere. So the taxonomy I have chosen will examine opportunities in the following categories. Artificial Intelligence Big Data On-Demand Care Everywhere Internet of Things Blockchain Contactless Healthcare Following is a brief explanation of each of these digital technologies as well as some examples of how healthcare organizations might apply these technologies to their daily operations. Artificial Intelligence: Perhaps the most hotly debated and widely used term in healthcare’s digital transformation is Artificial Intelligence, or AI. At its core, AI refers to the ability for computer systems to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, and data- dependent decision making. There are several sub-categories of AI, including, but not limited to, machine learning, natural language processing, computer visioning, 3-D printing, and robotics.1 The machine learning function enables a computer to collect and analyze huge amounts of data and use its phenomenal data aggregation capabilities to recommend optimal treatment approaches to patient care. Machine learning can also incorporate personal health and genetic data to recommend a “precision medicine” approach to care, that is, prescribing the most appropriate medications and recommending the right lifestyle and behavioral choices for a unique individual as opposed to treating the “average” patient. One of the more promising applications of AI in healthcare is in using “computer visioning” to diagnose and treat disease. The healthcare literature is replete with examples of how deep learning combined with computer vision has surpassed the human capability to accurately diagnose skin lesions and predict precancerous or cancerous tissue in breast images. Computer vision is also being used to assist surgeons intraoperatively to improve visualization, to guide surgical movements, and even to program robotic arms to make fine, precise motor movements that are impossible to make with the human hand. 3-D printing is a technology that uses digital images and computer-assisted drawing to create anatomically precise implants for joint replacements, dental restoration, and prosthetic devices. Big Data: A close cousin to Artificial Intelligence is the use of Big Data in making healthcare system-level decisions. Big Data refers to the ability for computers to accept and process large volumes of structured and unstructured data (like numeric data, photos, audio, video, monitoring devices, etc.) from a wide variety of sources and to quickly analyze those data to produce meaningful and actionable reports, information, and recommendations. Big Data has been used successfully to combine patient-level data with demographic and epidemiological data to develop predictive analytics for healthcare leaders.2 For example, by monitoring and predicting the likelihood of public health emergencies, Big Data can inform public health leaders of the next likely region of disease or illness outbreak, can prospectively advise supply chain managers on the need for proper supplies and equipment to manage the disease, and can allow on-site operations managers to adjust staffing to meet patient demand. As systems take on more population-level risk, Big Data can also empower population health managers with information and algorithms on how to risk-stratify and prioritize interventions with patients. In order to manage capitated or risk-based financial arrangements, health system administrators can use Big Data to analyze their system’s patient retention rates and in- or out-migration of patients to or from their hospital system. On-Demand Care Everywhere: Besides using Big data to predict COVID outbreaks, another aspect of the industry’s digital transformation was thrust into the limelight by the COVID-19 pandemic. On-Demand Care Everywhere, facilitated by telehealth, refers to the ability of a health system to meet the patient at his or her location and on his or her terms, as opposed to forcing the patient to physically come to the provider or facility.3 On-Demand Care Everywhere is expected by today’s healthcare customer and has been facilitated by the broad consumer adoption of mobile technology, the development of digital video, and the gradual expansion of broadband into underserved and rural areas. The introduction of 5G technology will further reinforce the interest in and demand for on-demand healthcare. Long-term reimbursement for telehealth remains a question, and demand for telehealth services, although significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels, has seen a marked decrease since March and April of this year. Nonetheless, On-Demand Care Everywhere is likely to see continued investment as forward-thinking system leaders realize its cost-saving potential and begin to consider it as a competitive advantage. Internet of Things: Internet of Things, or IoT, technology, which refers to the ability of physically disconnected objects and devices—things like smartphones, wearable devices, or even smart pills with embedded sensors—to “talk” to one another via the internet, has also experienced explosive growth in the healthcare industry. For consumers, items like Fitbits and Apple watches have moved beyond being trendy fashion accessories to being critical remote health monitoring devices. IoT technology allows patients to digitally transfer their individual-level patient data to their healthcare providers. In the home and outpatient environment, IoT technology empowers patients to take ownership of their personal health data, and, by extension, for their own health and wellbeing. In the inpatient setting, IoT can assist with wayfinding in large and complex care settings and can support digital “command centers” similar to air traffic control centers to monitor high-risk patients and to alert providers to warning signs which foreshadow the possibility of a significant patient event.4 IoT data can be used by health plans to monitor patients’ exercise habits, medication adherence, and compliance with recommended treatment regimens. Blockchain: One of the more controversial applications in the digital transformation of healthcare is the use of Blockchain technology. Blockchain is essentially a decentralized, distributed ledger of transactions (each transaction known as a “block”) linked together by cryptography which provides for increased security and transparency. The blockchain may be built as a public chain, which anyone can join, or a private chain, where access is controlled by the creator of the chain. Because Blockchain is a peer-to-peer network and there is no central repository of data, and because each transaction is immutable and must be consistent with other Blockchain transactions and validated by the majority of users in the network, conflicting information is automatically detected, data integrity is greatly enhanced, and the system is not susceptible to hacking. Most people associate Blockchain with the notoriety of Bitcoin and the cryptocurrency bubble. But Blockchain has more applications in the healthcare industry than just payment. Blockchain technology could be used to build secure credentialing databases for providers, to track supplies and drugs across the entire supply chain of manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, retailers and end users, and it’s already being used to build “smart contracts” which patients, providers, and payors can access to insure accurate billing, adjudication of claims, payment, and coordination of benefits. One potential clinical application for Blockchain is in using its secure data sharing capability to match clinical trials recruiters with patient interest and suitability in order to find the most appropriate patients for clinical trials. Although there are not yet any widely accepted models of using Blockchain to transfer or share Protected Health Information (PHI), there are public and private organizations like the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Care Services Corporation, and MedicalChain which are exploring how to do so safely and securely.5 Contactless Healthcare: The last area within the digital transformation realm that will be addressed here is Contactless Healthcare, which has numerous applications in the healthcare system, particularly in the Patient Access and Revenue Cycle arenas. Contactless Healthcare refers to the ability for the patient to enter the healthcare system without being physically present to register or pay for services. The healthcare industry is admittedly a laggard in this area and should take a few pointers from the banking industry or Amazon, the undisputed giant of contactless purchasing. Particularly in the COVID environment, consumers want to be able to access their provider or their facility in a “contactless” fashion, through mobile technology or on-line scheduling, thereby eliminating long lines to register and complete the all-too-voluminous demographic, medical history, medication usage, and payor information “paperwork” which is necessary to begin treatment. Many forward-thinking providers have already instituted patient portals and kiosks to simplify their registration processes. With contactless technology, providers can offer pre-purchase incentives, text-to-pay options, and streamlined admissions and discharges from care. During treatment, providers can implement immediate, integrated, point-of-service referrals to specialists or post-acute resources, thus enhancing continuity of care and patient experience.6 With the multitude of digital transformation alternatives available to providers and systems, administrators may wonder where to start or how to build upon existing technologies. Fortunately, there are some basic, time-honored management principles they can use to navigate the digital jungle. Here are a few recommended steps to start or enhance the digital transformation journey. First and foremost, envision and embrace the future. The undeniable fact that the healthcare system is already changing. More importantly, recognize that digital transformation is not only inevitable, it is also necessary for survival and desirable to streamline and improve the patient experience. In order to embrace the future, health system leaders will need to conduct a realistic assessment of the organization’s current digital business maturity and readiness for change. Second, set up a digital transformation governance team if one is not already in place. The governance team will establish a structure to understand and evaluate the myriad of technologies that are available and/or emerging. Members of the team may include system or hospital executives, finance and IT personnel, technical experts, process engineers, and biomedical specialists. Consider age and ethnic diversity and include millennial digital natives on the team. Involve functional leaders as necessary to understand and vet potential departmental options. Be sure to involve caregivers in the conversation; front line caregivers have a vital perspective on what currently works, what doesn’t work, and what could be possible. They are also invaluable in flowcharting current and future state processes. Establish system priorities. The governance team should create evaluation criteria and set up a prioritization matrix, considering factors such as patient safety and experience, cost, complexity, integration with existing systems and processes, potential provider acceptance or resistance, speed to market, and anticipated benefit to patients and providers. Administrators and financial management personnel can explore and report on the resource implications of a potential digital investment, and they can recommend those projects with the greatest clinical, operational, social, and financial return. Once priorities are established, chart a path for the digital journey. Develop project teams and report on project requirements, milestones, and communication points. Within each chosen project, clarify the required steps to implement change. Include a plan on how to gain organizational buy-in for the chosen technologies. Assure that affected staff members will be afforded an orientation and adequate training to fully understand, support, and implement the technology. Develop multi-modal communication to inform all stakeholders—patients, providers, staff members, partners, vendors, community members, etc.—of the impending change, including the timeline and intended benefits of the technology. Finally, execute the plan, allowing sufficient time for testing, validating and implementing the technology. Consider strategic partnerships and vendor relationships that align with the organization’s digital vision. If parallel processes are necessary during the testing phase, prepare the affected department for some redundancy of effort. Build in time and resources for technical setbacks or resistance to change. Frequently, a soft or partial roll-out is preferable to a full, all-at-once go-live. And, obviously, each organization should develop Key Performance Indicators to evaluate the success of its digital strategies. Lastly, celebrate successful digital product launches and project completions. Digital transformation is hard work, and staff should be complimented and rewarded for the extra effort of being digital pioneers. Clearly, this article has only scratched the surface in considering the possibilities of digital transformation in the healthcare industry. There are plenty of current challenges and issues we still need to address, like EHR interoperability, cybersecurity, inherently inefficient industry processes, and concerns about resource availability and ROI of digital investments. The opportunities are enormous, and the imperative for inquisitive, innovative, and thoughtful leadership is paramount. In considering the words “digital transformation,” this article has perhaps focused on the digital component of that term, but it will take truly transformational leadership to succeed. Notes: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/in-tmt-artificial-intelligence-single-page-noexp.pdf https://h20195.www2.hpe.com/v2/getdocument.aspx?docname=a00063521enw https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/09/MarketInsights_DigitalTransformation.pdf https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/life-sciences-and-healthcare/articles/global-digital-hospital-of-the-future.html https://www.digitalauthority.me/resources/blockchain-in-healthcare/ https://mpwrsource.com/wp-content/uploads/10_Best_Practices_for_Creating_an_Outstanding_Digital_Patient_Experience_-_Change_Healthcare-1.pdf

Published in South Florida Hospital and Healthcare Association Newsline – The specter of the novel coronavirus was just a pale shadow as the Florida Legislature held its sine die (dropping-the-handkerchief) ceremony on March 19, 2020, in the hallowed halls of the Florida Legislative Chambers. The Legislature had worked harmoniously to pass significant healthcare legislation and to deliver its constitutional mandate, a balanced budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year, even in the wake of the emerging COVID-19 threat. The Legislature’s proposed budget totaled $93.2 billion, the largest in the state’s history. In addition, major health care legislative accomplishments included: An expanded scope of practice for advanced practice nurses, in the hopes of improving access to primary care for Floridians; The ability for qualified pharmacists to enter into collaborative practice arrangements with physicians to simplify and enhance the treatment of Floridians afflicted chronic conditions like asthma, arthritis, obesity, and tobacco use, as well as test for and treat ailments like the flu, strep throat, lice and skin conditions like ringworm and athlete’s foot; A mandate for essential providers (like academic medical centers and safety net hospitals) to contract with each Medicaid managed care plan in their region in order to participation in Low Income Pool or other supplemental payments. No Medicaid rate cuts and the continuation of current Medicaid reimbursement methodologies and rates for inpatient and outpatient hospital services. In normal times, the Governor has 15 days to sign or veto legislation presented to him upon the conclusion of the legislative session. But these are not normal times, so, at the Governor’s request, the Legislature “held on” to some key legislation, allowing the Governor to focus his efforts on dealing with the effects of the virus. But during that time, COVID-19 raged and Florida became the new national hotspot. Tourism was dramatically affected, the economy was effectively shut down for a while, and it became increasingly apparent that the state would have a severe revenue shortfall in the coming fiscal year. Finally, the Legislature delivered its budget to the Governor on June 17, giving him two weeks to sign it or identify line item vetoes. Faced with a bitter fiscal reality, the Governor made some difficult choices on June 29, two days before the beginning of the new Fiscal Year on July 1, 2020. Unfortunately, a few meritorious healthcare projects were vetoed, including a proposal to increase the wages of healthcare workers who provide services to those with developmental or intellectual disabilities, and a proposal to increase Medicaid rates for providers who care for people with disabilities in institutions. Even with the Governor’s vetoes, however, which totaled more than $1 billion, the state faces a potential budget gap. Fortunately, the CARES Act, other federal legislation, and the ability to draw upon state reserves will help to plug the gap. In addition, although he has been loath to do so, the Governor has the ability to call a Special Legislative Session to address current year budget challenges. The final $92.2 billion budget approved by the Governor, shown as a pie chart below, still has healthcare as the largest sector receiving state funding.1

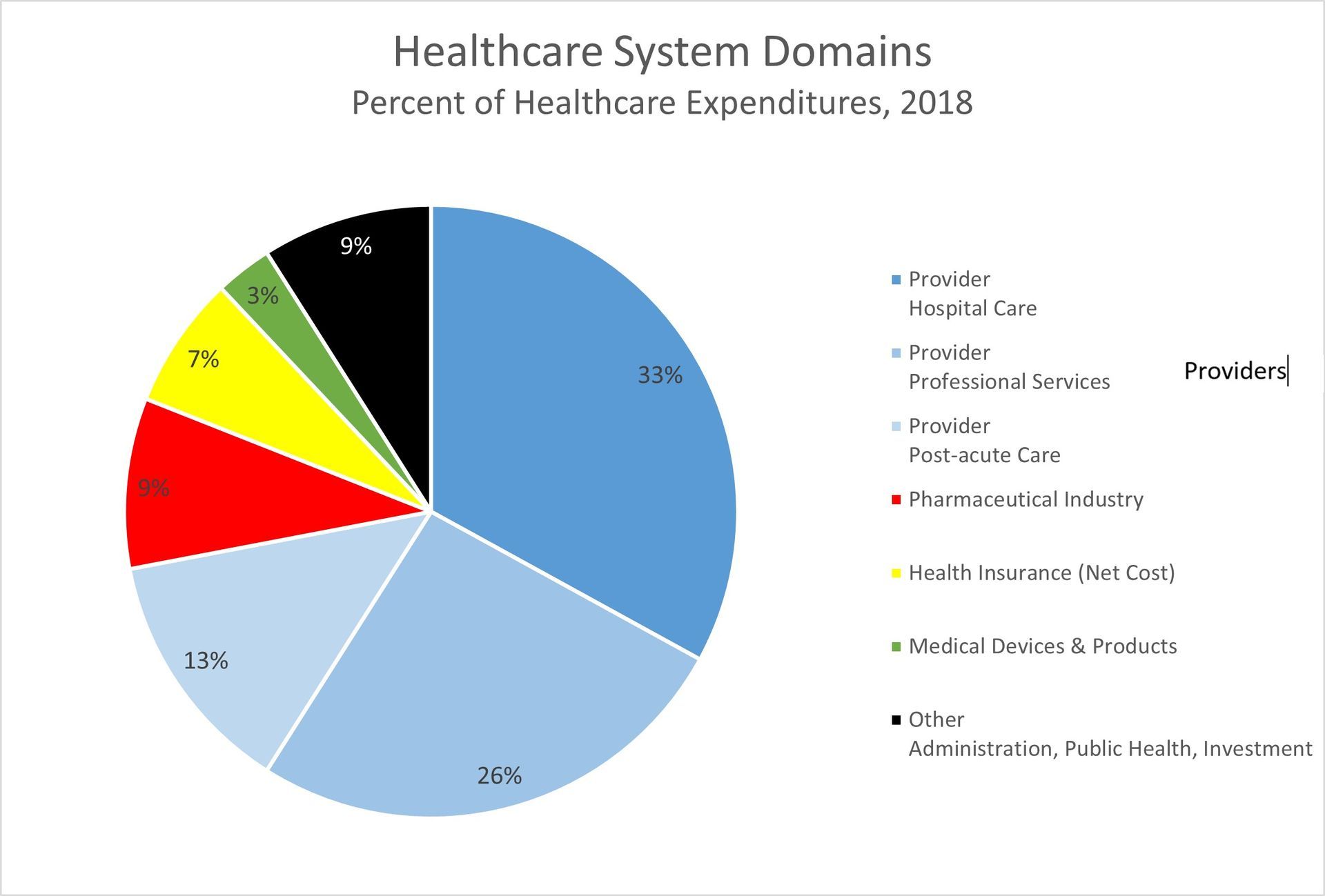

Published in South Florida Hospital and Healthcare Association Newsline – So here we are, seven or eight months into this thing, and we still haven’t quite figured it out. We know it’s deadly, we know it affects certain among us disproportionately, and, unfortunately, we know it’s not going to fade away anytime soon. We can see and feel some of the effects in our everyday lives—the heroism of our essential workers, the economic turmoil around us, the isolation of “social distancing,” and the tragedy of lives lost too soon. We know we’ll get through this, but not without some fundamental changes and impacts to our healthcare system. And it’s not just the provider sector of the industry that is struggling to adapt to the new normal and trying to anticipate what “recovery” looks like. The entire industry is undergoing fundamental change. As we look at the big picture, let’s see if we can understand some of the effects the pandemic has had so far, which might help us figure out where things might go from here. Rather simplistically, we can define our healthcare system as having four major domains,1 all of which have had some degree of impact due to the COVID-19 pandemic. By far, the largest domain is the healthcare delivery or provider domain, and this is also the domain that tends to drive the operations of the other major industry sectors. Here is the breakdown by domain.

Published in South Florida Hospital and Healthcare Association Newsline – Even in the middle of a pandemic, when hospitals are struggling financially due to the surge inbCOVID patients and the slowdown in ED visits, outpatient visits, and elective surgery cases, these same hospitals have been dealt a devastating 1-2-3 punch by HHS and the Courts. Here are a few examples: Price Transparency: The first major jab in this ongoing match between HHS and the hospital community came in late June of this year when Judge Carl Nichols, U.S. District Judge for the District of Columbia, upheld the HHS position and ruled against hospitals in a major price transparency case. Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, hospitals have been required by HHS to publicly post their chargemaster prices, supposedly helping consumers make more informed choices on where to go for care. But wait, hospitals argued, chargemasters don’t show the true price of care to an insured individual. Instead, the price of care is typically negotiated between the hospital and the insurer, with some (usually) small portion of the price being borne by the individual in terms of a copay or deductible. In this case, hospitals may become victims of their own argument. Back in June 2019, HHS developed and the President signed an Executive Order requiring that hospitals post the actual contracted rates with health plans for 300 “shoppable” procedures (including 70 procedures designated by HHS). In December 2019, hospital industry groups filed a lawsuit against HHS, contending that this transparency effort would undermine the free market and place hospitals at a disadvantage in contract negotiations. Judge Nichols, however, rejected that argument by saying that hospitals “are essentially attacking transparency measures generally, which are intended to enable consumers to make informed decisions; naturally, once consumers have certain information, their purchasing habits may change, and suppliers of items and services may have to adapt accordingly.” The American Hospital Association has announced that it will appeal the decision, which is currently scheduled to take effect in January, 2021. Site Neutral Payments: The next gut punch in the HHS/Hospital industry pricing saga came just last month, barely three weeks after the first. This time, Judge Srikanth Srinivasan, Chief Judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, issued a ruling upholding HHS’s authority to implement site neutral payments. As a bit of history, hospitals have enjoyed the ability to price outpatient services rendered at hospital-owned physician practices, surgery centers, and diagnostic centers at a premium by using the hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System, which pays significantly more than the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which physician-owned clinics are required to use. Hospital advocacy groups argued that the overhead of running a hospital as opposed to smaller, simpler business models like a physician practice or an ASC should justify these higher prices. However, physician groups, freestanding ASC’s, and HHS itself argued that Medicare and others should pay at a standard rate for the type of service performed, irrespective of the site of service. The hospital industry won an earlier court case in June 2019, but HHS appealed the ruling. This time, the Court agreed with HHS, stating that the financial interests of consumers outweighed the financial benefit to the hospitals and that the federal government should not be required to subsidize hospitals by paying more for a procedure at a hospital that at a non-hospital affiliated site. Preliminary projections show that this decision will deal an estimated $800 million annual financial hit to hospitals’ revenue streams.1 340B Payment Reduction: Just last week, Judge Srinivasan once again put hospitals on the ropes when he issued an Appeals Court decision to allow HHS to implement a 28.5% reduction in Medicare reimbursement for 340B drugs. Back in 1992, when the 340B legislation was first passed, Congress allowed eligible “covered entities” (including safety net hospitals) to purchase certain medications at discounted prices in order to ease the burden of providing significant amounts of uncompensated care. But the number of 340B sites and the volume of 340B drugs dispensed has grown dramatically due to hospital growth, hospital acquisitions of physician practices, and legislative action granting greater hospital access to the program. Today, about 1/3 of hospitals participate in the 340B program. Over the years, HHS came to object (1) that 340B sites could make the discounted drugs available to both compensated and uncompensated patients and (2) that it was reimbursing many of these 340B medications according to the Medicare Outpatient Fee schedule at much higher rates than it costs the organization to acquire the drug. When HHS developed a rule to lower 340B reimbursements and limit its financial exposure, hospital associations (predictably) sued. Again, a lower court ruling in November 2019 favored the hospital industry’s position that HHS had exceeded its authority in making the reimbursement cuts, but last week the Appeals Court saw it differently. This time, the adverse financial impact to hospitals is projected to be $1.6 billion annually, even worse than the site neural payment adjustment.2 So, you might ask, what’s going on? Doesn’t HHS recognize the vital role that hospitals are playing, putting their own financial futures at risk—not to mention the incalculable sacrifice of their staffs—as they serve on the front lines of combating the pandemic? HHS would likely argue that the timing is not of its making; these are longstanding court cases that are just now being decided. But timing aside, here are a few reasons why the U.S. government and its legal system are supporting these decisions, which are undeniably averse to the interests of America’s hospitals. First, the federal government is anxious to represent itself as the champion of the consumer in its fight against rising healthcare costs. Hospitals alone are not to blame for the skyrocketing cost of healthcare, but they do constitute the largest bucket (32.7%) of healthcare spending in the United States,3 and they therefore represent a huge target for cost reduction. The vulnerability of the Medicare program itself may be a driver of the repeated attempts to control the increase in federal healthcare costs. The most recent report from the Congressional Research Service indicates that, absent further legislative or regulatory action to control spending, the Medicare Trust Fund could become insolvent in 2026.4 It important to note that HHS’ onslaught on hospitals is not about the quality of care or even the availability of care that is being rendered by the industry; it is about the pricing of that care. By attacking pricing, which is near and dear to the hearts of consumers and taxpayers, HHS can hope to avoid the backlash from members of the public, who generally (and even more so now during the pandemic) recognize that hospitals provide the critical safety net within their communities. Sadly, it may be that HHS sees hospitals as an easier target than other formidable industry groups, like Big Pharma or the health insurance lobby. The pharmaceutical industry spends three or four times as much as the healthcare industry on lobbying efforts, and the insurance industry spends twice as much.5 Despite repeated rhetoric that drug prices are too high or that insurance companies control too much of the decisions and the dollars in healthcare, there have not been any meaningful attempts to reform the pharmaceutical or insurance industries in recent history. With these recent Court decisions, we in the healthcare industry may feel a bit battered and bruised. We are down but definitely not out. We know, however, that the road to financial recovery won’t be easy. Let’s continue to be good stewards of the resources we do have, but let’s also pick ourselves up, engage our stakeholders, leverage our political contacts, and educate our community about the challenges we face. When we have the opportunity to spread the word about our valiant efforts in saving lives and protecting the health and welfare of our community, we should use that same platform to enlist the understanding, aid, and support of our community leaders. As members of America’s most reliable, most essential, and most vital industry, we intend to keep it that way. Notes: https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/appeals-court-sides-hhs-site-neutral-payments https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/appeals-court-sides-hhs-drug-payment-cuts-340b-hospitals https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2018/043.pdf https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS20946.pdf https://www.investopedia.com/investing/which-industry-spends-most-lobbying-antm-so/

Published in South Florida Hospital News – A year ago, many healthcare transformation thought leaders were predicting that the greatest disruptors in our industry would be healthcare company megamergers or blue chip tech companies entering the healthcare delivery market—like CVS’s acquisition of Aetna, Apple’s foray into personal health records and interoperability, or Amazon’s empowerment of Alexa and acquisition of PillPack. Probably none of them would have named the novel coronavirus as the biggest prospective change agent in the industry. But here we are—smack in the middle of a COVID-19 pandemic—and many of the medium- to long-term effects of the virus have become apparent to those of us in the field. Here’s a glimpse at some of the trends and impacts on the healthcare industry from COVID-19: the good, the bad, and the ugly. The Good: Telehealth: From Wall Street to Main Street, one of the most significant effects of the pandemic has been the explosive adoption and acceptance of telehealth as a means of delivering healthcare services. Healthcare delivery was already moving out of the four walls of the hospital into outpatient sites of care and even into retail settings. But COVID has brought providers to the desktops and mobile devices of mainstream America. Some estimates indicate that, as of April 2020, telehealth (defined as synchronous video conferencing, “store and forward” of digital medical data, and remote patient monitoring) has grown by 80% year over year1, spurred on by the relaxation of telehealth guidelines and reimbursement restrictions previously adopted by public and private insurers. Sure, there are still challenges to address—like continuation of these looser reimbursement policies, interstate licensure and credentialing issues, broadband access in rural areas, etc.—but the horse is out of the barn and there’s no turning back now. Telehealth has the ability to positively impact healthcare in many ways, including creating greater access to primary care, abating the overcrowding in the ED, and enabling a better quality of life for chronic disease patients. Most systems have already invested heavily in telehealth; those that haven’t need to catch up quickly. Self-care and family care: Despite some mixed and often diffuse messaging from public health authorities early in the pandemic and the occasional deliberate flaunting of social distancing guidelines by segments of the population, by and large, most Americans are embracing more personal responsibility in the care of themselves and their loved ones. Mainstream America is now adopting many of healthcare’s sacred principles like frequent handwashing, cleaning and sterilizing one’s immediate environment, and adopting practical infection control practices (think masks, gloves, etc.). In addition, baby boomers and Gen X-ers are becoming steadily aware of the hidden hazards of congregate living for their parents, and they are increasingly choosing noninstitutional settings for their aging or disabled family members. Even though these family members may be homebound, they often lead a more dignified, more comfortable, and happier life than their counterparts in more institutional settings. Innovative hospital systems like Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore or Adventist Health in California have created Hospital-at-Home programs (virtual hospitals) which feature video visits and remote patient monitoring by hospitalists to enable patients to remain in the comfort of their own homes during their hospitalization and convalescence.2 Occupational Health and Safety: Employers are becoming increasingly aware of their new responsibilities to provide a COVID-free work environment (and their potential liabilities if they do not). Federal and state courts are already seeing a dramatic rise in the number and types of COVID -related lawsuits, including cases related to workplace safety, workers compensation, and employees in high risk settings.3 Many employers have responded by dramatically reducing business meetings and travel and by converting as much interaction as possible to virtual settings. For those employers who need on-site employees, there is a renewed interest in employee health and safety, to wit, a dramatic rise in plastic protective shields for frontline personnel, the provision of PPE for essential workers, more robust disinfectant processes for common areas and equipment, and the reconfiguration of offices spaces to allow for more social distancing. The pandemic provides the opening for health plans, healthcare providers, and occupational health and safety professionals to play a larger role in executive conversations, facility design, and employment practices.4 Artificial Intelligence: Before the pandemic, we had already seen the promise of AI in healthcare applications like using supercomputers to interpret radiology scans or identify skin lesions5, employing machine learning to aggregate and analyze huge amounts of diagnostic data to aid in accurate cancer diagnosis6, and applying real-time data analytics to speed up the healthcare revenue cycle7. But the pandemic has hastened the adoption of AI areas not heretofore imagined. For example, health departments are using AI to analyze large amounts of public health data to identify and predict new virus hot spots and to develop early warning systems, clinicians are using chest imaging data along with AI-enabled EHR data to improve risk stratification and to categorize the type of care COVID-19 patients receive8, and pharmaceutical manufacturers are using AI to accelerate vaccine research. Look for AI to be adapted to many more clinical and operational aspects of healthcare delivery in the future. The Bad: Effect on Medical Practices and Hospital Volume: The traditional bastions of healthcare delivery—the doctor’s office and the hospital—have been hit particularly hard during the pandemic. One MGMA study showed that 97% of all medical practices have endured a financial hit, some with revenue declines of 60% or more.9 Many physician practices have had to furlough or eliminate staff and cut their own salaries; many will not survive at all. This will further exacerbate the already growing physician shortage and further limit access to those needing care. Hospitals have had a double whammy: eliminating or reducing profitable elective surgeries while simultaneously treating resource-intensive (but comparatively low-reimbursing) COVID patients. And despite the CARES Act and other federal assistance, many hospitals, particularly safety net institutions, are facing huge cash shortfalls and will be severely limiting capital expenditures for growth initiatives for the foreseeable future. Smaller, independent, and rural hospitals are particularly at risk for their survival. M & A activity, which was already strong prepandemic, is likely to increase as stronger organizations and institutions absorb the more financially-strapped providers. Government officials and private insurers should closely monitor the situation and be prepared to provide relief in the form of advance payments, expedited reimbursement, and grant funding when warranted. Delays in Care: Some studies indicate that near ½ of all Americans have delayed seeking care because of loss of income and the fear of infection from COVID.10 The negative consequences to the patient for not obtaining timely care can result in needless suffering and death. There are already signs that cancer rates are rising rapidly and caregivers are seeing more deaths from heart disease than expected.11 In addition to patient effects, the impact to healthcare organizations will also be significant. Time and again, research shows that delays in seeking care result in poorer clinical outcomes and more expensive hospitalization costs. Despite losing their profitable selective surgeries and service lines, healthcare organizations need to prepare now for the demand that has been suppressed by the pandemic. When bed capacity allows, healthcare organizations need to encourage and reassure those who have delayed care; to do so, they need to beef up their infection control processes and convince their patients that they are ready for the “new normal” of treating patients in an institutional setting. As they do so, recognize that this pent-up demand will probably result in more acute care episodes, longer lengths of stay, and higher costs. Uptick in mental health and substance abuse conditions: The pandemic has not only created a greater need for behavioral health interventions; it has simultaneously upended the already patchy and fragile continuum of care for mental health and substance abuse patients. Even as 40% of Americans have reported that stress related to the coronavirus has negatively affected their mental health,12 staffing crises and shortages of protective supplies have caused a reduction in mobile crisis teams, residential programs, and behavioral health call centers. Also, during the pandemic, there has been a surge in alcohol sales and a dramatic spike in opioid deaths. Social distancing, for all the good that it has done in society at large, has imperiled social connection and support for addicts and has jeopardized their recovery. Some relatively novel interventions have cropped up, including community-led and family-led interventions, more robust remote therapy, and technology-enabled collaboration platforms for primary care and behavioral health providers.13 We as a healthcare system need to continue to find new ways to address the depression, isolation, and drug use exacerbated by the pandemic and to create treatment modalities which are safe and effective in dealing with behavioral health conditions. The Ugly: Disparities in Care: COVID-19 has laid bare the ignominious underbelly of our healthcare delivery system; that is, that vulnerable populations are more at risk for contracting the virus and less likely to recover. COVID-related morbidity and mortality for Black, Latino, and native Americans are three to four times higher than for white Americans.14 Although genetic or biological factors may have some small bearing on these statistics, the more likely explanation lies in the longstanding cultural, social, and environmental conditions associated with these ethnic and demographic groups. Societal factors contributing to these disparities in disease incidence and hospitalization rates include housing conditions, income, education, and wealth gaps, access to healthcare providers, and inherent societal discrimination.15 Healthcare executives alone can’t be expected to fundamentally undo the years of socioeconomic injustice. They can, however, be vocal proponents of health equity and should be proactive in identifying and rooting out any vestige of inequitable care in their organizations. They can also use their position in the community to reach out to underserved populations, to promote positive policy changes, to address social determinants of care, and to espouse socially-conscious healthcare delivery. Public Health and Health System Preparedness: Finally, COVID-19 has also exposed the potholes and gaps in our public health system. Clearly, there were miscommunications in our early minimization of the potential magnitude and dangers of the virus and missteps in our uncoordinated response efforts. Confusion between state and federal responsibilities, lack of communication among large federal agencies (such as the CDC, the FDA, and FEMA), state public health departments, hospitals, private laboratories, and equipment suppliers led to a suboptimal rollout of diagnostic testing and a lag in ensuring that hospitals had adequate personal protective equipment and ventilators. Ultimately, this delay and confusion resulted in lost time and lives. But the problem goes deeper than interagency or state/federal miscommunication. Simple complacency or a false sense of security led to an erosion of our public health infrastructure. As far back as 2000, the Institute of Medicine issued a report entitled “Public Health Systems and Emerging Infections: Assessing the Capabilities of the Public and Private Sectors,”16 warning that diminished funding levels and lackluster support for the American public health system, particularly at the state and local levels, would lead to diminished capacity to predict, detect, and respond to an emerging infectious disease. Despite this warning and others like it, the last decade has seen a further reduction in the spending on the public health infrastructure and a decline in the public health workforce by more than 15%.17 Even in the wake of SARS, Zika, Ebola, H1N1, and now COVID-19, the CDC has seen relatively flat funding for the past 10 years.18 As citizens, we should demand accountable leadership; and as healthcare leaders, we should rally for appropriate reinvestment in our federal, state, and local disease surveillance and response systems. So there you have it. COVID-19 is a devastating and deadly disease, and it has tragically impacted us (as of late July) with over 4 million cases and over 146,000 deaths19—and that’s just in the United States. It continues to dominate our news cycle, our economic recovery, and, indeed, our very lives and livelihood. But it has also impacted us in ways we never imagined. We have learned that the pandemic has implications not just in healthcare, but in social justice, economic well-being, international cooperation, and world order. As much as we might want to put the pandemic in our rear-view mirror, let’s not let this experience be for naught. Let’s capitalize on our successes, learn from our failures, and candidly look at the opportunities to improve our preparedness and response efforts for the next inevitable disruptor in healthcare. Notes: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/telehealth-market-us-reach-revenues-150000310.html https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/hospital-home-programs-improve-outcomes-lower-costs-face-resistance https://www.natlawreview.com/article/employers-beware-covid-19-related-employment-lawsuits-are-heating https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payer/optum-survey-employers-leaning-health-plans-to-assist-return-to-workplace-initiatives https://www.theimagingwire.com/2019/05/09/googles-imaging-ai-breast-cancer-predictor-watson-imaging-goes-live/ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304383519306135 https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/artificial-intelligence-benefits-revenue-cycle-management https://healthitanalytics.com/news/artificial-intelligence-could-speed-covid-19-detection-treatment https://www.mgma.com/data/data-stories/covid-19%E2%80%99s-impact-on-provider-compensation https://khn.org/news/nearly-half-of-americans-delayed-medical-care-due-to-pandemic/ https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMms2009984 https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-americans-feeling-anxious-especially-for-loved-ones-older-adults-are-less-anxious https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(20)30307-2/fulltext https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html? https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22953360/ https://www.astho.org/StatePublicHealth/COVID-19-Highlights-Need-to-Fund-State-Public-Health/04-01-20/ https://forensicnews.net/2020/03/10/ https://covidtracking.com/data

I spent most of my career as an executive in hospitals and healthcare delivery systems, witnessing firsthand the incredible work of the physicians, nurses, technicians, and the healthcare support teams I was privileged to lead. More recently, I have become involved as a healthcare consultant in Florida’s public health system; in that role, I devote my efforts to encouraging and facilitating healthy environments, healthy behaviors, and healthy lifestyles for the members of our Florida communities. And I have become convinced that the public health teams of researchers, community health workers, environmental engineers, disaster response specialists, contract managers and policy advocates are just as passionate, just as committed, and just as concerned about “population health” as their colleagues in the field of healthcare delivery. Now, more than ever, there is a confluence of issues related to both public health and healthcare delivery. Even before COVID-19, both fields shared the challenges of dealing with healthcare-related societal issues—gun control, natural and man-made disaster preparedness and response, anti-vaccination fears, tobacco-related smoking and vaping prevalence, elimination of race-related health disparities, and controlling the spread of communicable diseases like Hepatitis, Measles, and HIV/AIDS. Public Health has long been concerned about health equity (so much so that it is a basic goal of the State Health Improvement Plan) and has identified priority populations which require additional resources to achieve optimal population health. Likewise, healthcare delivery administrators and practitioners are now recognizing the outsized impact that social determinants of health—availability of adequate nutrition, access to reliable transportation, degree of family support, stable housing status, to name a few—have on community heath status and actual clinical outcomes. And, of course, now we have COVID-19 to reinforce to us how important it is that professionals in public health and healthcare delivery come together to tackle the most important issue of our era. We have been rudely reminded that public health is still an evolving science as we grapple with the uncertainty around the novel coronavirus—mode(s) of transmission, adequacy and length of antibody protection, “shelf life” of the virus, which types of personal protective equipment are most effective, necessity and/or degree of social protective measures, and side effects of potential vaccine and treatment pharmaceuticals. What is inarguable, however, is that the brave healthcare workers on the front lines bear some of the greatest burdens in caring for the most vulnerable members of their communities. Their burdens include a risk of personal infection, a likely forced separation from family and loved ones to minimize viral spread, shortages of requisite supplies and equipment, and the untold emotional toll, and resultant burnout and PTSD, associated with long hours and the strain of working in an environment replete with death and disease. So how best as a system of healthcare should we address the challenges both inside and outside our respective institutions? Can we as public health and healthcare delivery professionals develop a shared vision of population health which bolsters both institutional prosperity and community health? Of course we can; here are a few steps we can take. As a first order of business, Let’s do everything possible to protect, support, and reward the healthcare delivery workforce, that is, those who are charged with providing care and contributing selflessly to the health of the community. This goes beyond ensuring safe staffing ratios, providing adequate PPE, and storing reservoirs of supplies and equipment; it means truly addressing the emotional health of the workplace and the mental health conditions that often follow stress and fatigue, like depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress. Utilize the public health resources that are available, adopt institutional policies to support mindfulness and stress reduction, develop a back-up workforce of volunteers or retirees, and devote additional resources to providing healthcare workers with crisis intervention, hotlines, psychological support, and telepsychiatry. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/mental-health-healthcare.html https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7156943/ https://www.bmc.org/healthcity/policy-and-industry/healthcare-workers-protect-mental-health-covid-19 Empower your employees to become public health advocates and agents of change. Arm them with information and make them available personally or virtually to community organizations and policy makers. Let them share their personal stories of tragedy and triumph to illustrate the positive effect of public health initiatives or the need for further policy change. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/AFC_Manual_01.pdf https://connect.springerpub.com/content/book/978-0-8261-4834-6/part/part01/chapter/ch02 https://www.reflectionsonnursingleadership.org/commentary/more-commentary/Vol42_2_influence-through-advocacy-raising-awareness-advancing-change Collaborate with one another and with public health officials to address current challenges. One of the links below shows the example of collaboration among healthcare leaders in Florida to address the COVID-19 surge. As healthcare leaders, we can sponsor community forums (virtual, if necessary) to stimulate meaningful discussion among public health and healthcare professionals, business leaders, media representatives, and state and local legislators. Let your clinicians provide guidance to the community and share the message of personal and corporate responsibility to help address and eliminate disparities in care. https://www.tampabay.com/news/health/2020/04/17/rivals-in-normal-times-tampa-bay-hospitals-battle-the-virus-together/ https://www.lsuhsc.edu/administration/academic/cipecp/docs/Collaboration%20between%20Health%20Care%20and%20Public%20Health.pdf https://www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/article/january-february-2013/public-health’s-role-collaborating-for-healthy-communities Advocate for social justice and pragmatic change. The lay community is hungry for healthcare leadership and knowledge. Recognize that your responsibility for spearheading and facilitating that change extends far beyond the historical four walls of your institution into the fabric of the community. https://www.apha.org/what-is-public-health/generation-public-health/our-work/social-justice https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1053 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4006198/ https://online.regiscollege.edu/blog/healthcare-social-justice-movement/ Being a public health or healthcare delivery leader today comes with unprecedented challenges but incalculable rewards. By getting out of our respective comfort zones, reaching across the aisle, protecting and empowering our workforces, and calling upon the guidance and wisdom of professionals from both disciplines, we can come together to achieve our collective yet ever-elusive goal of optimal population health.

Published in South Florida Hospital News – We certainly have our share of challenges in the health care industry these days. In fact, I am hard-pressed to remember a time in my career when the issues are more daunting and pressing than they are today. Never mind the ambiguity associated with the bumpy roll-out of the Affordable Care Act or the ever-constant reimbursement pressures brought about by governmental and private payers alike. Now we have true public health challenges like the diagnosis, treatment and containment of Ebola and the alarming incidence of the D68 enterovirus (EV-D68) among children, along with our more long-term, chronic issues like the growing prevalence of obesity (particularly among children), chronic diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Some of these issues are the result of the inevitability of our demographics: an ever-aging population combined with a growing shortage of primary care physicians, nurses and other skilled caregivers. Although certain trends seem to be moderating somewhat—like the cost of lifesaving pharmaceuticals and technology and the lack of financial and geographic access for the underserved—we are not out of the woods yet. In fact, many governmental and private payers are now trying to shift patients out of an inpatient status into an outpatient status, essentially paying hospitals less for providing the same care and using the same resources. Add to that the increasing competition in the healthcare provider industry from traditional players (to wit, Ambulatory Surgery Centers, Diagnostic Imaging Centers and Urgent Care Centers) as well as surprising and even disruptive players (like Walgreens, CVS and even insurance companies). And, unfortunately, our industry is plagued by the historical inability and/or unwillingness to communicate (electronically or otherwise) among the disparate members of the health care continuum, including physicians, hospitals and other mental health and ambulatory providers. Together, these challenges present a tsunami of unprecedented proportions which we, as health care providers and stewards of our communities, need to address pragmatically and collaboratively. We do have new models and constructs for addressing some of the challenges facing us. Think about it. We now have the emergence of a new breed of health plan (accountable care organizations), value-based purchasing of care by insurers, clinical integration initiatives among providers, the development of electronic health insurance exchanges to facilitate greater access, and new care coordination models with health care extenders acting as personal navigators between patient and providers. And we have new tools in our arsenal: telemedicine, patient engagement portals, performance improvement methodologies (Lean, Six Sigma), electronic health records with improving interoperability among systems, quality and utilization monitoring software to improve the quality and the access of the care we provide. We are supported by our professional societies and organizations, like the “Choosing Wisely” campaign endorsed by over 60 medical societies and organizations to encourage candid conversations between providers and patients about the best course of care for the patient’s condition, and the “Partnership for Patients” campaign endorsed by the Hospital Engagement Network, with a goal of reducing patient harm by 40% and readmissions by 20% over a two-year period. These new tools, models and intersocietal support will help us achieve our community and institutional goals of better health, more popularly known today as “population health,” manifested in a reduction in hospital readmissions, the minimizing of hospital-acquired infections, the optimization of core “process” measures (doing the right thing at the right time to the right patient, every time) and the eventual improvement in community public health indicators. But one of the fundamental changes that need to occur in the health care continuum is the breaking down of the silos in our health care delivery system. We need to work with the state and federal government to develop and align the incentives of providers as we change our model of care. We need meaningful conversations, not just among providers, but with the financiers of care; that is, governmental payers, commercial payers, and, yes, even with business leaders and employers, who are often the ultimate payers of care. Especially in today’s information age of emails, texting, social media and impersonal mass media, we need face-to-face discussions with one another and with our key stakeholders and customers on how to improve the health of our community. We need the development of partnerships and affiliations based on mutual trust and a shared vision. As we do so, let’s not forget the central element in all of our discussions, the patient and his or her family support system, and let’s be deliberate about educating them on their roles on the health care team and including them in our brainstorming and our planning for the future. This will require bold action and innovation by us, as health care executives, to demonstrate leadership, commitment, open-mindedness, a healthy dose of humility and perhaps a bit of sacrifice. This is our real challenge and, hopefully, our pathway to better health.

Published in South Florida Hospital News – Healthcare Organizations Provide Fertile Ground for a Crisis